Bass players get no respect. Unless the bass player of a band also happens to be its lead singer, people don’t generally know much about the bass player, let alone their name. For example, prior to the preparations for my History of Rock class, I could not have told you who Bill Wyman was (he’s the primary bass player for much of The Rolling Stones’ time together). James Jamerson – the prolific session bass player for Motown in the 1960’s – is one of the more influential figures in the direction of popular music, yet I would contend that a vast majority of people do not know who he is. Bass players’ contributions, though often foundational for the sound of their group, often go unobserved and are almost always underappreciated.

With that in mind, allow me to sing the praises of one of the more underrated individuals from the 90’s rock scene: Robert DeLeo. Robert is the bass player for Stone Temple Pilots (his brother, Dean, is that band’s guitarist), but he is also their primary songwriter (though lyrics are often left to the band’s vocalist, Scott Weiland). Aside from being a talented and influential bass player, Robert is also responsible for some of the most intricately composed songs from the grunge era of rock and, in fact, the entire history of rock.

Stone Temple Pilots are unmistakably grunge – their dark, crunchy guitars; riff-based songs; splashy, heavy drums; use of light and shade; and emotive vocals are all trademarks of the genre. Because of the deeply personal and dark attributes of grunge music, I feel that many of the artists from this genre are underappreciated for their musical contributions. This is not entirely unfounded – with such distorted guitar tones, it can be difficult to hear specific pitches from their harmonies. However, among all of the grunge artists, STP (and specifically, Robert DeLeo’s writing) stands out for their subversive implementation of advanced musical techniques, particularly in their harmonic and rhythmic sophistication.

STP’s catalogue is full of songs that exemplify these techniques, but for sake of simplicity, let’s focus on five of the songs from their sophomore 1994 album, Purple.

“Meatplow”

As the lead track off Purple, “Meatplow” (most grunge song title ever?) sets the tone for STP’s harmonic adventurousness quite literally with the riff that kicks off the track (Ex. 1):

The opening four pitches (E-G-A-C), follow a somewhat conventional pentatonic pattern (they would be scale degrees 3-5-6-1 in a C pentatonic scale), but the shock comes when it becomes clear that the riff’s primary modal center is F#. With these pitches centered around F#, they outline an F# Locrian mode, which is a mode built around the seventh pitch of a major scale (or a natural minor scale with both lowered second and fifth scale degrees). Because of the highly unresolved nature of the seventh scale degree, this mode is easily the least commonly used of the seven diatonic modes, and it is the only one that features a diminished fifth between its first and fifth notes instead of the much more consonant perfect fifth. Most of this riff follows a fairly conventional rock/blues technique of alternating between the modal center and a whole step below it, but this opening four-pitch pattern adds a significant degree of modal complexity that makes the riff sound much fresher.

The harmonic complexity of “Meatplow” only increases when chords are introduced for the first time during the song’s prechorus. This section features a three-chord progression that starts with a shift to a B chord. A pivot to a four-chord (IV) from the song’s mode is a common tactic for a rock song; however, both the quality of this chord and the chords that follow it in the progression add substantial harmonic sophistication.

Prechorus:

Bsus | CMaj(#11) | FMaj(#11) | FMaj(#11) | Bsus | CMaj(#11) |

As a chord consisting of the pitches “B-E-F#”, the harmony outlines a B chord but swaps the third for a suspended fourth above its root (“E” instead of “D” or “D#”) and thus gives the music a very ambiguous sound. This chord then moves to the pitch collection of “C-E-F#”, which shifts the previous chord up a half-step to a C major chord with a raised fourth (indicated as an upper extension #11 in the chord symbol). Essentially, the harmonic second between E-F# is maintained while the chord root moves up a half-step from “B” to “C”. This interval pattern is then maintain but transposed down a perfect fifth to the pitch collection “F-A-B” in the following measure. The previously static “E-F#” pitch tandem is now omitted, but the sound of a Major third and a Major second from the previous chord is maintained, moving here to an FM(#11) chord.

Because these chords all feature harmonic seconds and upper extensions while also minimizing tertial harmonies, they are fairly dissonant sounds independently of each other. When taken in the context of their harmonic progression at this point in the song, we find yet another layer of harmonic sophistication. Keep in mind that the verse was in F# (and F# Locrian, at that). While a pivot to a B chord brings the music to a conventional IV chord, the C and F chords that follow it really have no logical function in that mode. Furthermore, there’s not really a different mode that would comfortably house all three of these chords. The Bsus and CMaj(#11) chords perhaps imply G Major (flat-two of the F# Locrian mode), but the FMaj(#11) chord doesn’t work in that mode. My belief is that the most logical mode for the prechorus is E Major – in this mode, the Bsus would be a V chord, the CMaj(#11) would be a modally borrowed bVI chord, and the FMaj(#11) a flatted II-chord (or Neapolitan chord). This is admittedly a stretch, but a progression rooted around V-VI-II fits somewhat within chord progression conventions. More importantly, this progression is an indication as to how fascinating this small stretch of the song is.

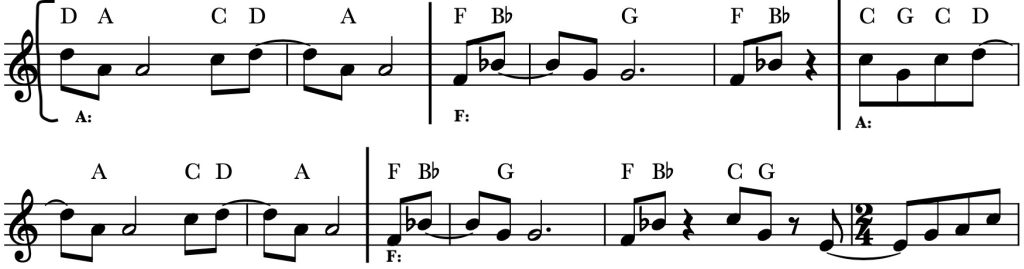

On final unique aspect of the prechorus as it leads into the chorus is the length of this section, which is six measures. The initial four-bar progression, which holds the FMaj(#11) for two measures), repeats, but instead of returning to the FMaj(#11) chord, the CMaj(#11) pivots into the chorus by moving up a whole step to a D major chord. By breaking the symmetry of the phrase, STP makes the jump to the chorus surprising because it includes a shift in both phrasing and mode. The chord progression for the chorus is diagrammed below (Ex. 2) with Lead Sheet Symbols above the staff, with pitches in the staff reflecting chord roots and rhythms used to indicate when chords change within a measure. Key areas and the points of modulation are also highlighted below the staff for the purposes of the analysis that will follow. The primary meter is 4/4.

Every chord played in the chorus is a major triad. While on the surface this seems to be much more consonant than either of the previous sections, the fact that there are so many different kinds of major triads used in the chorus means that there is a lot of modal ambiguity to sift through. There are six different major triads in the chorus (D, A, C, F, Bb, and G chords), and while all six of these pitches would fit within a single mode, these major triads do not. Once again, there is not a clear way to analyze these chords, but my ear tends to hear the first two measures conforming to A Major and the second two in F Major (with a pivot back to A Major at the end of the fourth measure). In this analysis, the D and A chords in the first measure are IV and I, while the C would be a modally borrowed bIII. The F chord in the second measure marks the shift to F Major, while the Bb and G chords would be IV and V/V (a secondary dominant chord tonicizing a V chord) in that key. The C and G chords at the end of the fourth measure would be bIII and bVII in A major.

However, even as I write that, I find myself second guessing my analysis. Why wouldn’t the chorus start in D Major since the progression begins on D? In the key of D, this progression would go I-V, which makes a lot of sense. In this instance, I settled on A because the bIII-IV progression makes a bit more sense than bVII-I as I am hearing it. Similarly, for the third measure, there is an argument to be made for Bb Major rather than F Major, though in neither key is the G major chord diatonic.

But herein lies the fun of analysis and the brilliance of this song in particular. Music exists on a spectrum, and it is a lot of fun to explore the grey area within that spectrum when given the opportunity to do so. How do I know what key this chorus is in? I don’t know that I can know for sure, largely because I am guessing the members of STP did not conceive of it that way. Not knowing and embracing the uncertainty is what makes music such a fascinating journey, and I love when artists, especially ones I wouldn’t expect, let me explore that uncertainty.

STP saves one final surprise for the end of the song in the form of its final chord. The last chorus ends with the opening four-pitch riff that leads into an F# Major chord, which is the same resolution as the previous two choruses. However, after landing on this F# Major chord, the band unexpectedly shifts down a half-step to end on the F Maj(#11) chord from the prechorus. This is the only time in the whole song that they move between these two chords, and it is also highly unusual for them to finish the song on arguably its most dissonant chord and the one that is furthest removed from the song’s primary modal center.

“Vasoline”

The second track from Purple, which was also its second single, is the churning neo-punk rocker “Vasoline”. Although this song is much more restrained harmonically than “Meatplow”, it still possesses ample complexity, particularly in its use of rhythm.

Perhaps the defining musical feature of “Vasoline” is the two-pitch guitar/bass riff that begins the song (after an ethereal guitar fade in and an entrance of the propulsive drum groove) and drives the verse sections. Alternating between “F” and “G” and played under a static G major chord (the song’s tonic chord) strummed by an acoustic guitar (which enters with Scott Weiland’s vocals), the riff is certainly steeped in a blues tradition. Its short-long rhythmic pattern presents a 3-against-2 hemiola over the song’s 4/4 meter that gives the music a syncopated energy. However, what stands truly unique about it is the degree to which the riff commits to this hemiola. During its first statement prior to the vocal entrance (0:29), it repeats this pattern for six whole measures before resetting with sustained pitches in the seventh and eighth measures. The riff restarts at the beginning of the verse (0:40), but this time it repeats all the way through the eighth measure, not breaking until holding out its final long note slightly longer on the upbeat of beat 2 in the eighth bar in order to hit the downbeat of the chorus (0:52).

The first chord change does not happen until the chorus, when the harmony moves from the static G major chord to an Eb major chord, which is a modally borrowed bVI chord. This chord holds for three-and-a-half measures before walking down chromatically to a C major chord in the fifth measure of the chorus, which would be a diatonic IV chord. Before returning to the main riff and its static G major chord, the C chord jumps down to an F major chord (modally borrowed bVII) in the eighth measure with a syncopated rhythm that effectively restarts the main riff’s hemiola. Traces of the short-long syncopated hemiola can also be detected in the vocal melody of the chorus, which starts the first two measures of each phrase in the chorus with a short-long-long rhythm. Although this doesn’t maintain the original riff’s commitment to the hemiola, it does serve as a link between the two sections. As with the chorus in “Meatplow”, these chords demonstrate STP’s inventive technique of implementing a variety of major chords – diatonic and non-diatonic – to achieve unique chord progressions.

Chorus:

Eb | Eb | Eb | Eb-D-Db-C | C | C | C | C-F |

The third distinct section of “Vasoline” is the song’s bridge (1:49), which is also alluded to in the song’s fade in intro. Like the verse, this section features one static chord, although this chord is sustained above its active drum groove and does not feature the rhythmic hemiola in the main guitar part. However, this chord is neither diatonic to the song’s key nor a triad. Dean DeLeo is playing a Bb major seventh chord with a #11, which would be a modally borrowed bIII M7(#11) chord. This abrupt chord shift lends the song an unusually bright sound, particularly with its used of raised 7 and 11, implying a Lydian modal sound. This is further emphasized with Weiland’s final melody note of the bridge (1:58), where he sustains the #11 pitch “E” before resolving it to the more consonant “D” on the return of the main riff (2:00) for the guitar solo.

The other unique aspect to the bridge is a new guitar/bass riff that is a bit more hidden within the texture. This riff is actually very similar to the main riff in that it alternates between two pitches (“A” and “Bb” this time) in the same short-long hemiola pattern, but because the lead guitar line (or at least the one brought up the most in the mix) holds out chords, it comes off a bit more subversively than the main version of the riff. Along with Weiland’s nod to the short-long pattern in the chorus, this gives every section of the song a link to its main rhythmic motif.

One final connection between this song and “Meatplow” is that both end on very unusual chords. “Vasoline” ends on the BbM7(#11) chord from the bridge, which gives the song a somewhat unresolved but very bright sound. Using a chord that is both non-tonic and non-diatonic to end the song is yet another subversive technique STP is using to provide a unique quality to their music.

“Vasoline” became STP’s first #1 single on the Billboard Album Rock Tracks chart (currently known as the Mainstream Rock chart), spending two weeks in the top spot. To find the song that dethroned it, you only need to look ahead two tracks on the album…

“Interstate Love Song”

Although the fourth track from Purple was released as its third single, “Interstate Love Song” was easily the biggest hit from the album. The track displaced “Vasoline” from the #1 spot on the Album Rock Tracks chart and remained there for a staggering 15 weeks in 1994, which was a record at the time for that chart.

Like “Vasoline”, “Interstate Love Song” starts off with a blues-inspired riff (Ex. 3) played over a static tonic harmony (E Major here), although this riff is much more melodic than the one in “Vasoline”.

What is most unique about this riff is its treatment of rhythm. It uses a hemiola rhythmic pattern similar to the one used in “Vasoline” as it starts with four consecutive dotted eighth note rhythms spread across the first three beats of the riff (or the equivalent of an eighth and sixteenth note tied together). These are followed by a full beat of sixteenth notes that reestablishes the metric pattern, but then the second measure returns to the dotted eighth rhythm of the first measure. It ends up getting used just once, though, and its use in the second measure is more of a syncopation than a hemiola. This combination of rhythms creates a unique energy against Eric Kretz’ plodding backbeat groove that recalls the dichotomy of Led Zeppelin’s interplay between the riffs of Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones and the constancy of John Bonham’s backbeat (“Black Dog” is a great example of this) and gives this riff much of its memorability. The other distinct aspect of rhythm in this riff is the fact that it occupies three measures rather than two or four, which makes it subtly asymmetrical. This is actually itself a clever modification of another blues technique. The blues form is a repeating 12-bar structure, but these 12 bars are broken into three four-bar phrases. In a classic blues style, the first two of these phrases are often very similar, while the third offers contrast/resolution of the initial idea. Here, STP starts with a descending riff in the first bar that resolves up in the second bar, and then it nearly restates that second bar in the third. So instead of the “aab” pattern of blues, they are using “abb” in the pattern for this riff.

Aside from this highly memorable riff, much of what gives this song its identity is its combination of sophisticated harmonies and crunchy, grungy guitar timbres. Overdriven 90’s guitar tones are often muddy enough to prevent the clarity necessary for too complex of chord qualities, which is a significant reason why these songs tend to utilize open-fifth power chords. This is also why this sound is so refreshing in STP’s music, and “Interstate Love Song” is a great showcase for this.

As with the previous STP songs, this song relies heavily on major chords (though not exclusively so here), but what is unique is that its progressions are more conventionally diatonic. Well, mostly. Several chords are actually not diatonic to E Major, but the ones that are not are probably best understood as secondary dominant chords that connect to diatonic chords within the key rather than as modally borrowed chords. The chord progression for the verse is provided below:

Verse:

C#m | G#+/B# | C#7/B | F#7/A# | Aadd2 | E | E |

After starting with a vi chord in the song’s key of E Major, we get an unusual augmented triad with the pitches “G#”, “C” (though technically B# in the context of the key), and “E”. Although this chord is built on the third note of the song’s key of E Major, its B# makes it a secondary dominant chord that tonicizes the vi chord (C# minor), or V+/vi. The most common use for augmented triads in a popular music context is as an alteration of a V/dominant chord with a raised fifth from the chord’s root, and so this analysis as a secondary dominant chord accommodates for that usage. This chord then resolves to its tonicized C#, but instead of a minor chord, we get a dominant seventh chord (C#7/B). This is also a secondary dominant chord, and this one tonicizes a ii chord (V4-2/ii – the 4-2 accounts for the chord’s inverted voicing). The next chord does something very similar – it goes to the expected chord root of F#, but once again it changes it from a diatonic minor chord to a dominant seventh chord (F#7/A#). This chord tonicizes B (V), which would make it V6-5/V. This is the one secondary chord in the progression that does not move to its expected destination – instead of going to a B chord, it moves instead to an A major chord with an added second (Aadd2, or IV). The “add2” does at least include a “B” in the chord, even though it is neither its root nor a part of the foundational triad. The progression then resolves to tonic, which also includes the final portion of the intro riff played over it.

Although this is largely a chord progression with conventional function, its use of altered and extended chords gives it a very unique sound. Only the starting and ending chords are conventional major or minor triads, while all the chords between these feature an augmented triad, two different inverted dominant seventh chords, and an add-2 chord. The other unique aspect of this progression is the chromatic voice-leading it features, which is highlighted by Robert DeLeo’s descending chromatic bass line. The bass begins the verse on the root of the first chord in the progression (“C#”) but then moves in descending half-steps until it hits the root of the Aadd2 chord. In doing so, it moves through different inversions to create more interesting sounds for these chords. Robert DeLeo is also embellishing this chromatic movement with a James Jamerson-esque melodic bass, which adds a touch of soul to create yet another subtle shade to the sound. This chromatic bass movement serves as an interesting contrast to the mostly static “E” pitch found in the top voice of Dean DeLeo’s guitar chord voicings. This “E” holds steady through every chord except the C#7/B, which moves up a half step to an “F/E#” to accommodate the chord. Such voice leading recalls techniques found in Bach chorale writing, and it lends the track a subversive sense of sophistication.

The progression for the chorus is a bit more conventional with its use of harmony, as it features nearly all diatonic root position triads. Its use of both G#sus and G# major chords gives the progression an unexpected lift, however.

Chorus:

C#m | E | A | G#sus – G# | A | E | A | G#sus – G# | A | E |

Diatonically, the progression begins with vi, I, and IV chords, all used conventionally, but the two types of G# chords in the fourth measure provide a bit of a twist. The use of the suspended chord (G#-C#-D#) that resolves halfway through the measure (G#-B#-D#) lends a tasty moment of tension and resolution to an inner voice. The G# Major chord to which the suspended chord resolves is itself not a diatonic chord, but rather a secondary dominant that tonicizes the key’s vi chord (V/vi). However, this chord instead resolves to a IV chord, providing an ascending half-step shift from one chord to the next. This resolution of V/vi – IV is a fairly common exception in contemporary rock/pop music, so this is hardly an Earth-shattering musical moment. It is still a neat wrinkle, and when paired with the previous suspended chord, it works effectively to distinguish this very catchy progression. Even in arguably their most radio-friendly song, STP is still finding ways to set themselves apart.

“Pretty Penny”

Although “Pretty Penny”, which is the sixth track from Purple, was released as the fourth single from the album, it essentially had no lasting impact on rock format radio stations, and personally, I have never heard it played on any FM stations. Still, it continues many of the unique harmonic techniques observed in previous tracks on the album, and particularly when considering its approach to rhythm and meter, it might be the most unique track on the album.

Even though the folk-waltz vibe of “Pretty Penny” sets it apart stylistically from the grunge-y “Meatplow” and the punk-adjacent “Vasoline”, all three songs share many harmonic characteristics. All three songs have verses that are harmonically very static. “Pretty Penny” has the most active chord progression for its verse sections, but even it is limited to two chords that alternate throughout its duration.

Verse:

E5 – Esus4 | GMaj(#11) |

These chords toggle between E and G chords, but a closer look at their respective qualities reveals some interesting nuances. The E chord is qualitatively ambiguous, and while it features two different voicings, neither features a pitch that is a third note the chord’s root. The initial presentation of this chord uses only an open fifth between “E” and “B”, while a second version is added halfway through the first measure that adds an “A” to these two pitches. This A makes the chord a suspended chord (similar to the one used in “Interstate Love Song”, but because the implied chord is minor and the note to which this “A” resolves is a “G”, it perhaps sounds more like an “add 11” chord rather than a suspended chord. My notation calls it Esus4 for the sake of simplicity, but really the guitar chords are walking the upper voice “B” down stepwise to “G” by adding the “A” in between. Because this chord is so bare, though, it creates a notable color shift in doing so.

The G Major chord that follows it is also more complex than it might initially seem. In addition to the three pitches of a G major triad (“G”, “B”, and “D”), they have added a raised 11th (“C#”) to give the chord a very bright sound, but it also creates a Lydian modal sound that heightens the folk-like aspect of this song. By adding this dissonant pitch, they are also obscuring the modal centrality of the music. The song can be heard in either E minor or G Major, but the fact that its E chord is missing the quality-defining third means that the G Major chord sounds more like the harmonic destination. The fact that this chord adds the raised 11th adds complexity to this understanding, though, as such a dissonant chord sounds less like harmonic resolution. This is also similar to the chord found in both “Meatplow” and “Vasoline”, and it is further evidence of STP’s subtle use of harmonic coloration to achieve a more sophisticated sound.

The song’s chorus is even more harmonically static than its verse, as the chorus stays static on a A Major (#11) chord – a whole step up from the second chord from the repeating verse progression. This new chord adds more complexity to the modal understanding of this song, as this chord is not found in either E minor or G Major. My reading of the song is that the verse and chorus are in two separate modes – the verses are in G Lydian, while the chorus shifts up to A Lydian.

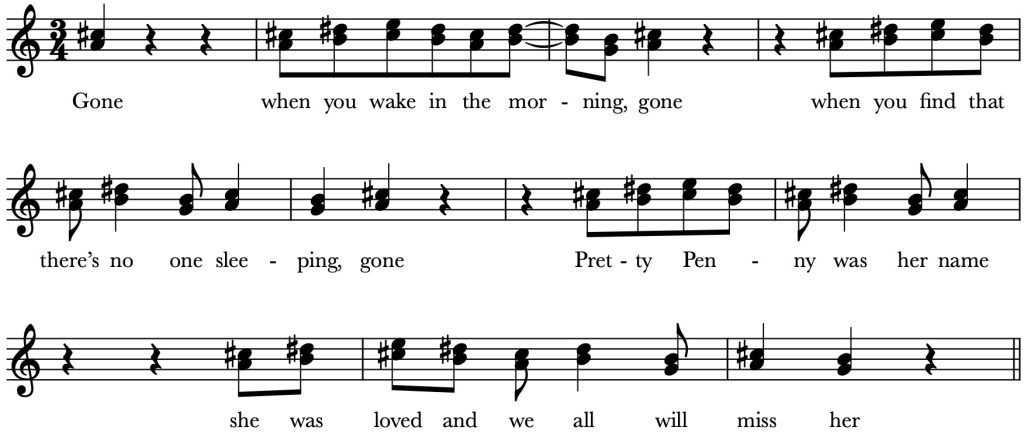

Perhaps the most unique aspect of the chorus, however, is its use of meter and rhythmic organization. The chorus seems to continue the simple triple meter of the verses, but each phrase consists of three three-measure (perhaps recalling the phrase length of the riff from “Interstate Love Song”) and a fourth phrase that is only two measures. At 11 measures, this is a highly unusual phrase construction. Transcriptions of both the repeating three-measure guitar part and the sung two-part chorus melody in this meter can be found below (Ex. 4, 5):

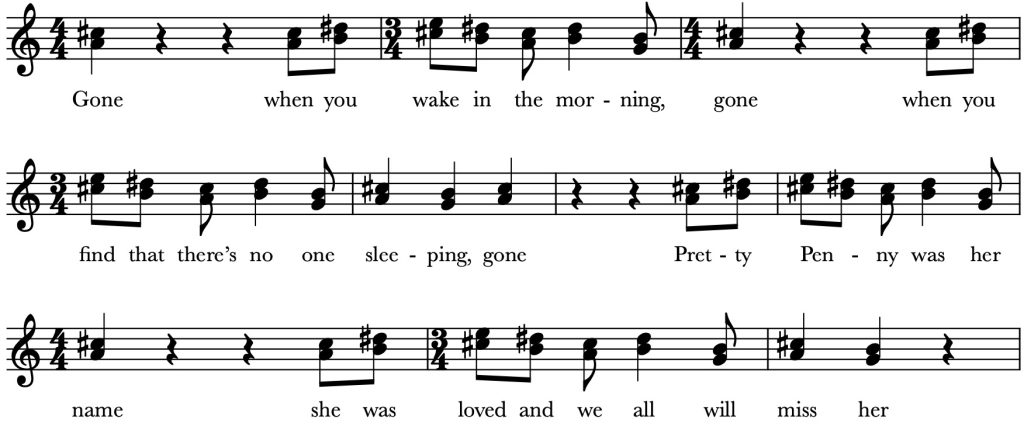

When I listen to this part of the song, though, something does not quite feel right about this metric alignment. Specifically, it does not feel like Weiland’s vocal phrasing (Ex. 5) lines up with Dean DeLeo’s strumming pattern (Ex. 4). It is my contention that this section is actually polymetric, and the vocal melody exists in a different meter pattern not only from the rest of the song, but also from the rest of the band during the chorus. A modified version of the chorus melody appears before with the implied metric pattern of the vocal part (Ex. 6):

The chorus begins with a single attack on its first downbeat on the word “gone”. This word is very clearly on the first downbeat, but the next vocal phrase feels off in the existing metric pattern. When heard entirely in 3/4 time (Ex. 5), the eighth notes that start the next part of the vocal melody begin on beat one of the second measure, but to my ear these notes sound like pick-ups into a downbeat rather than the downbeat itself. The word “wake” receives a little more emphasis, and the fact that its pitch is the highpoint of the phrase leads me to hear it as being on beat one. This pattern returns with each subsequent line of text from the chorus, but in the original triple meter, it starts on different beats each time. The second and third instances begin on beat two of their respective measures, while the fourth and final occurrence falls on beat three.

In Ex. 6, I have adjusted the meter so that each of these phrases begins as a pick-up, with the third (and highest) note of each phrase beginning on a downbeat. This produces a meter patter of 4-3-4-3-3-3-3-4-3-3, with a few instances of 4/4 needed to align everything correctly. What is incredible is that despite these vocal twists and turns, the base rhythm established by the acoustic guitar does not change and remains in a triple meter with three-measure phrases. In this light, the harmonic stasis of the chorus proved necessary to lock in the wandering nature of the vocal melody. By using two meter patterns simultaneously (or, at least, having a vocal melody that intentionally phrases against the song’s primary pattern) while also incorporating harmonic dissonance, STP has created a hypnotic and delightfully disorienting sound within an otherwise pastoral setting.

“Big Empty”

This bluesy ballad is the eighth track off Purple, but despite its placement towards the end of the album and relaxed feel, it was released as the lead single off the album. This probably has more to do with the fact that the song was featured on the soundtrack to The Crow, which came out prior to Purple, than the song itself, but it was still a modest hit for the band, climbing as high as #3 on the Billboard Mainstream Rock Tracks chart and continuing to be a staple on rock radio stations.

The bluesy vibe of the song is reinforced by a few distinct musical attributes. For starters, Dean DeLeo’s backwoods slide guitar fills give the music a Delta blues feel. This is further enhanced with the harmonic vocabulary, particularly in the way they are utilizing upper extensions. As in previous songs presented in this analysis, the amount of unique chords in this intro and verse progression is minimized, but they use unusual chord voicings to add complexity to the progression.

Verse:

Em7(#11) | C9 |

The intro and verse imply an E minor modality and feature an alternation between tonic (i) and submediant (VI) chords. The tonic chord, however, adds two upper extensions – a minor seventh and a raised eleventh, which makes the chord Em7(#11). The submediant chord is played as a dominant seventh chord with an added ninth (C9). Both of these chords feature the pitch “Bb”, which is notable because this pitch does not belong in E minor. Instead, it is the blue note, or flatted 5th/raised 4th scale degree, that is found in the blues scale and used extensively in blues music. Therefore, this emphasis of the blue note provides yet another link to the blues.

One additional unique aspect to the way STP is voicing these chords is that, despite the fact that they are playing E and C chords, they are featuring G triads at the top of both voicings. The higher strings of the rhythm guitar part strum a G Major triad (G, B, and D) for the Em7(#11) chord, and this shifts to a G minor triad (G, Bb, and D) for the C9 chord. These voicings utilize the upper extensions of both chords, but because of the triadic structure of the G chord they are using, it sounds as if they are playing two chords simultaneously. So not only are they playing complex chords, they are also dabbling with polychords through their careful use of chord voicings.

This polychordal approach is continued with the song’s chorus, which shifts the modal center from E minor to its relative major of G Major. Using the “light and shade” technique popularized by Led Zeppelin and featured by most grunge bands, Eric Kretz’ emphatic drum fill sparks the shift to crunchy guitars and a major key with the arrival of the chorus.

Chorus:

G – A | C |

G – G7/F | E7sus – E7 |

The chord progression for the chorus features three chords across two measures – G Major, A Major, and C Major triads. Of these chords, G (I) and C (IV) are diatonic to G Major, while A would be a nonfunctional secondary dominant chord (V/V) that resolves to IV instead of V. This is not all that uncommon of a use of this chord in popular music, and it creates a descending half step movement between scale degree 5 from the I chord, raised 4 from the V/V chord, and scale degree 4 from the IV chord.

What is most unique about the way STP uses this progression is, once again, the voicings that they use in their guitar parts. The highest guitar part in the texture is one that plays a static G Major chord (or at least an open fifth of “G” and “D” – it is difficult to hear if a “B” is between that fifth or not) over all three chords. Obviously, this is not unusual against the G Major chord at the beginning of the chord, but it fits less clearly against the A and C Major chords. This is especially true with the A Major chord, as the “D” in the static G chord clashes quite strongly against the “C#” within the A Major chord. However, because the static G chord is voiced apart from and above the defining chords of the chord progression, this dissonance is not obvious to the listener. This use of polychords in the chorus extends the technique used in the verse but offers another nuanced shading of it.

Before returning to the verse, the chorus concludes with a transitional chord progression that returns the modal center to “E” in a roundabout way. This progression reestablishes the current modal center with its G Major triad, which then shifts to a G dominant seventh chord with an “F” in the bass (G7/F), which would functionally be a secondary dominant chord that tonicizes C Major (V4-2/IV). As with the A Major chord used in the chorus, this chord does not resolve as expected, and instead it shifts to an E chord. This would seem to establish E minor, but this chord starts as a suspended chord before resolving not to an E minor chord, but an E dominant seventh chord. So although this transitional progression does culminate by tonicizing “E”, it does so with a modally ambiguous dominant seventh chord. This use of a tonicizing dominant seventh chord is another example of the song’s blues influence, which features mostly dominant seventh chords, including as modality-establishing chords. The other disorienting aspect of this pivot back to the verse is that the verse progression does not start on the E minor chord but, rather, the C7 chord, meaning we are delayed getting our resolving E minor chord by two chords in the progression.

After another statement of its verse and chorus sections, “Big Empty” then expands upon the short transitional section at the end of the first chorus by repeating the progression and adding a new vocal line (on the lyric “conversations kill”). The fourth statement of this progression ends on the suspended E chord and does not resolve it, and this then sends the song into its bridge. The bridge is entirely instrumental, and it is harmonically static. The mode shifts back to E minor; however, rather than a conventional E minor, they instead use the Dorian mode with a raised sixth scale degree (“C#). This mode shift is pronounced by the melodic C#-D-C# guitar riff that is sprinkled throughout the bridge, and it presents yet another variety of an E mode in the song in addition to the E minor of the verse and the E dominant seventh chord at the end of the transition linking the first chorus to the second verse.

Conclusion:

Taken altogether, Stone Temple Pilots incorporate numerous advanced harmonic and rhythmic techniques in ways that gives their music an individualized sound without removing it from its genre entirely. They are using techniques like upper harmonic extensions, nonfunctional harmony, polychords and polymeters, and numerous others to create a dense tapestry of nuance in their music. The fact that they do this while still incorporating heavily distorted guitars and deeply emotive vocals that are trademarks of early 90’s grunge music is incredibly fascinating to me. These techniques are not specific to the songs from Purple, but the album that is lauded as their critical and commercial highpoint has earned its reputation not just for having catchy songs but also for showing how Stone Temple Pilots can flex excellent musical chops.